[I] Whether European, Chinese or Brazilian, art critics and commentators of Partenheimer’s work often point to the meditative, aerial, carefree, imaginative and even lyrical nature of his drawings and paintings, never failing to mention the enigmatic balance which makes his work and the silence that appears to inhabit it so highly recognizable (consider the Roman Diary, Carmen, De Coloribus, and Zur Grammatik series or Die fragilen…

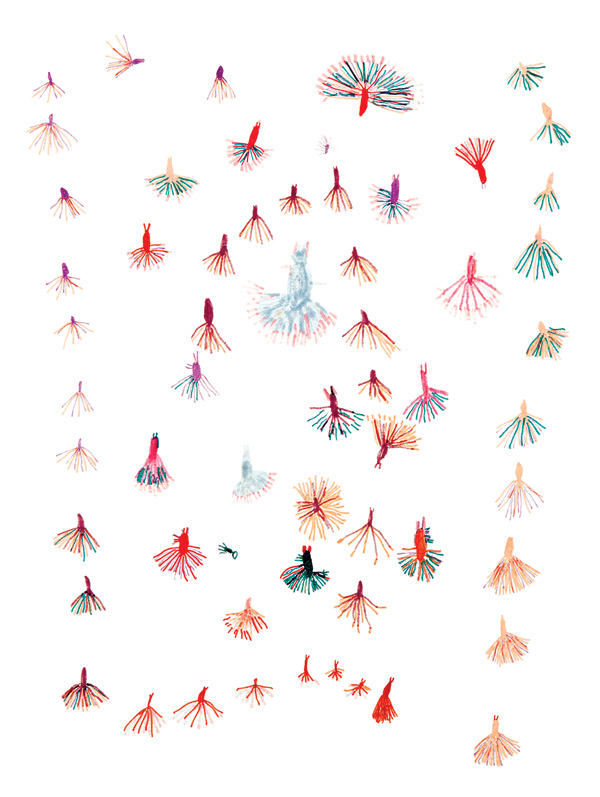

The Yanomami drawings are, literally, extraordinary. For aesthetic criteria, but also, and mainly, for their intriguing and mysterious character, when we stop to think about how and by whom they are made.

The images that the reader-viewer can appreciate in the preceding and following pages constitute a small sampling from the collections of Carlo Zacquini and Claudia Andujar, two tireless defenders of the Yanomami territory and people, with whom they have maintained close ties for decades. It was Andujar who in the 1970s brought them paper and colored pens—which they had never seen before—and asked them to use these materials as a means of expressing their world and their understanding of the world. As a form of communication.[1]

[1] In 1978, Claudia Andujar, Carlo Zacquini, and Emilie Chamie published a very beautiful book of Yanomami drawings, entitled Mitopoemas Yãnomam, sponsored by Olivetti do Brasil.

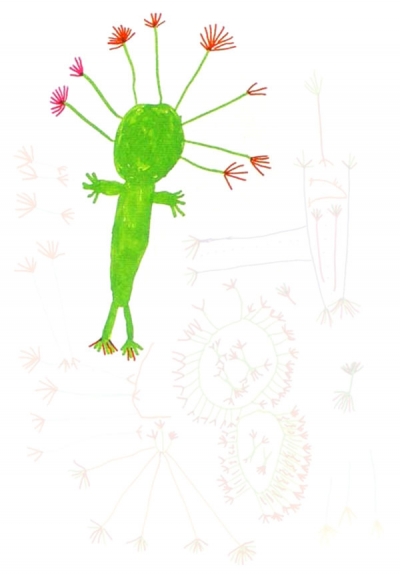

The Yanomami did not know about drawing, at least not as we understand it. Or to put it better, their culture considers forms of expression that involve the conception and execution of graphic signs, such as body painting and the ornamentation of baskets and other objects. But, according to anthropologist Bruce Albert—who thoroughly knows the life and thought of the Yanomami people—such graphic signs should be considered as traces or marks, not as images. Moreover, they are imprinted on bodies and objects—therefore, on volumes—rather than on two-dimensional surfaces like sheets of paper, which evidently changes everything. Thus, what we see here are drawings mad by people who do not “know” how to draw, who never learned and were not used to seeing drawings. These are not part of their ontological or epistemological universe. And this is where the intriguing fascination arises. Because when we become aware of this, certain questions immediately emerge: how is it possible for the drawing to happen? And how can there be so much power of expression, such an intensity of the line, so much balance and movement, so much vibration? In short: how can nonartists be able to create something so splendid?

The criteria of the history of art to which we normally recur are inadequate to explain the quality of this production. And to say that these drawings are “inspired” does not help to explain it. Nevertheless, it is patently obvious that the Yanomami seem to have direct and spontaneous access to the extreme freedom of the line, the act of drawing sought by Miró, or by Klee. From whence comes this grace? (There is no better term to describe what paradoxically drives the act of creation while seeming to result from it.)

Convinced that the Yanomami are great (non)drawers, great (non)artists, I decided to put their creations to the test. I wanted to check whether the extremely high quality I saw in them was a subjective question, an overestimation, due to my involvement with the Indians.[2] I trusted the longstanding aesthetic impression that they had caused over the years and through my daily experience with the drawings—but I wanted to compare it with that of a great artist, not committed with the Yanomami or the indigenous cause, that is to say, an unrelated reference point. This occasion arose in 2010, on the eve of the opening of the 29th Bienal de São Paulo.

[2] I have been in contact with the Yanomami since the 1990s, initially by way of the Comissão Pró- Yanomami (CCPY), an NGO founded by Claudia Andujar, Carlo Zacquini, Bruce Albert, and Alcida Ramos, which fought for the demarcation of their land, and later for the defense of the territory and culture of the Yanomami people. More recently, from 2008 to 2010, Davi Kopenawa, the Yanomami shamans, and the Watoriki community participated in the realization of the multimedia opera Amazonas, presented at the Munich Biennale (In- ternational Festival for New Music Theatre) and at Sesc Pompeia, in São Paulo. In 2011 and 2012, on the initiative of Davi Kopenawa, two meetings of shamans were held, within the scope of the Dispositivos de Visão project carried out by the Laboratório de Cultura e Tecnologia em Rede, of the Instituto Século 21, which resulted in the film Xapiri, codirected by Leandro Lima, Gisela Motta, Stella Senra, Bruce Albert, and myself.

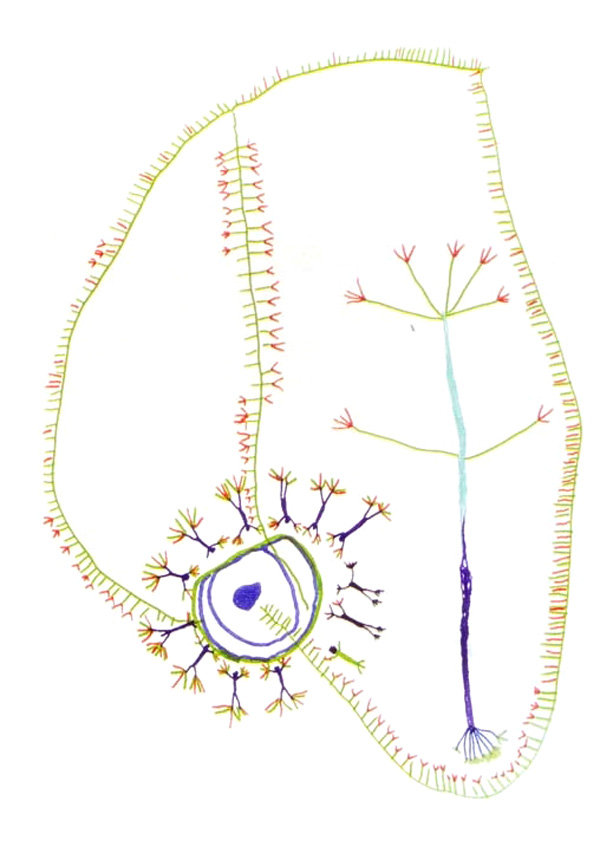

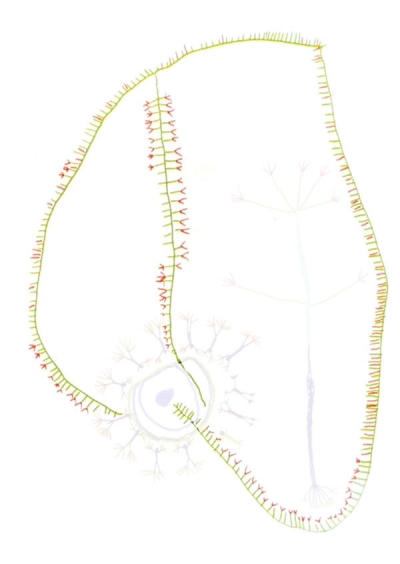

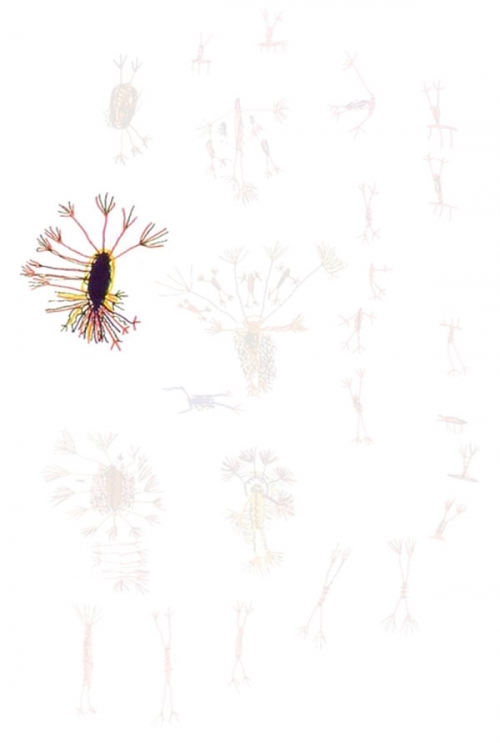

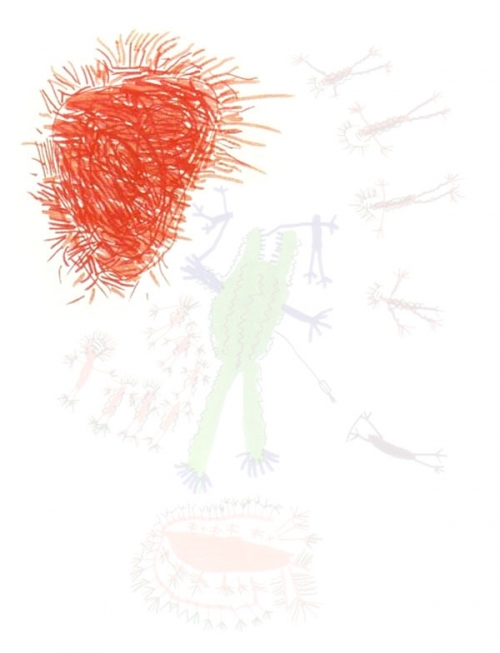

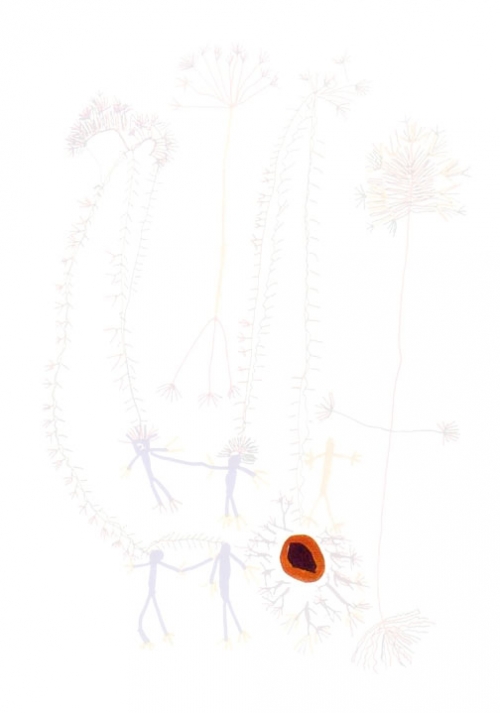

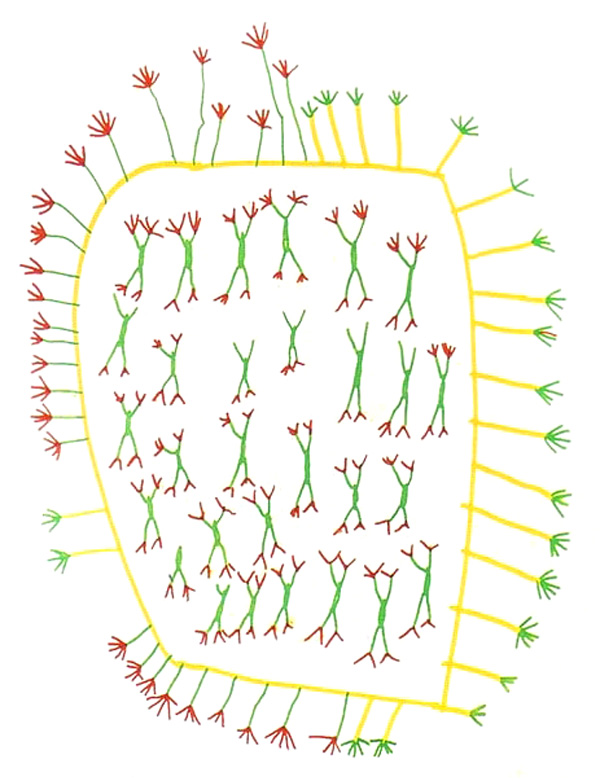

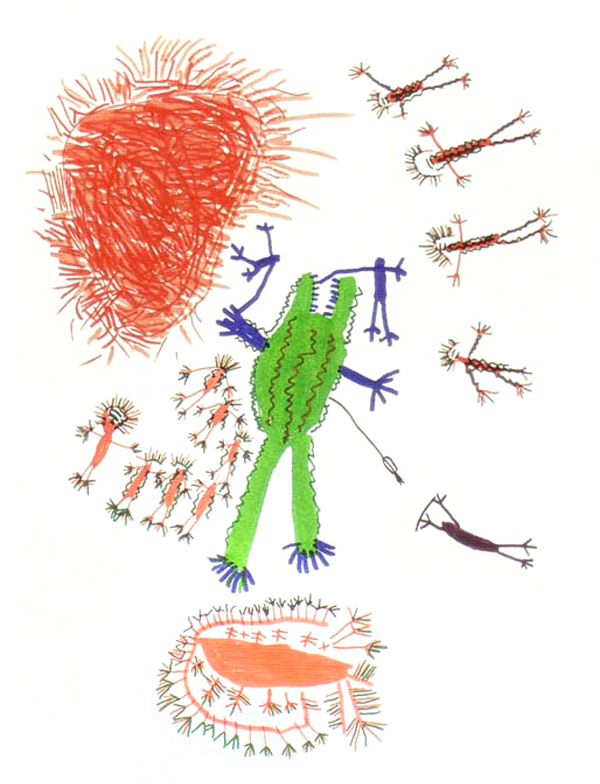

draw 36 Orlando

Subtitle

- Shaman Yanomami – Xapuri ñanomami

- Dish – Mahe a

- Powder of the Kurare – Ñakona uxip

- Path of the spirits of shamans – Hekura xapuriño

- Tree of the Kurare – Ñakonahi

Note: The subtitles are on the back of the drawings. Later on, some few words were spelled differently accordingly to linguistic studies of the Yanomami language. We chose to transcribe the wording as it appears in the original drawing (even when we cannot find the word in dictionnary) in order to stress the originality of the collecting of those drawings and their meanings in the 1970’s. When the information appears only in Portuguese, the term Yanomami was included, after consulting

LAUDATO, Luís. “Glossário” in Yanomami pey këyo: o caminho yanomami. Brasília: Universa, 1998.

Francis Alÿs was in the city, to set up his Tornado, and the opportunity arose to show him Claudia Andujar’s collection. It was then possible to observe how the works would be seen by a true master of the line. The artist—whose ability to concentrate and allow himself to get involved with everything around him is notable—looked intensively at drawing after drawing, delving into that universe. His engagement was evident, but he made no comments, except to ask Claudia Andujar some information about them. When he had seen about sixty to seventy drawings, he stopped and said he preferred not to continue, to prevent his experience of sight from being compromised by the excess. And he described his impressions. He said that what most caught his attention was the way the drawing occupied the entire sheet of paper, whether it was large or small; how their lines and figures, whether they filled the entire field or not, extended up to the borders. In his understanding, the way that this drawing activated the space was radically different from the experience of Western drawing, which always looks loose on the page, always exists as a fragment, never as a whole. It was clear that what most surprised Francis Alÿs was the way that the drawing was drawn; it was the movement that extended through the space, taking it over completely. And suddenly he discovered the thought that went into the process of their making: he perceived that the drawings were not constituted as compositions, as is normally done, but as projections of images that were wholly figured and configured, no matter if they arose from the outer world or from the spirit of the drawer. The artist perceived that the hand of the drawer and the eye of the viewer were the operators of an inaugural act, the act of the passage of an image that up to then had not been outwardly manifested as such, but which, upon being projected, found on the sheet of paper a space to be resolved. This gave rise to the drawing’s awesome integrity, and the affirmation of a never-before-seen totality. For this reason, Alÿs considered that the drawings were precious, unique.

The experience of watching the artist as he was observing the drawings was very important, not only to confirm my previous aesthetic impression, but also, and mainly, because this experience itself consisted of a happening that arose to mediate the occurrence of the image-drawing. As though the resolution that crystallized the discovery of the image-drawing’s singularity would decipher, for us, the resolution of a mode of artistic existence of which the Yanomami are the agents. A mode of magical existence.

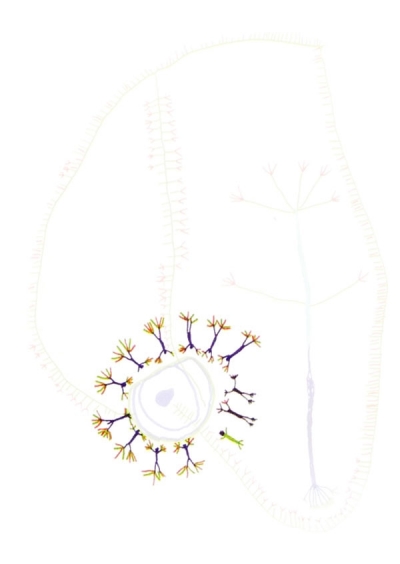

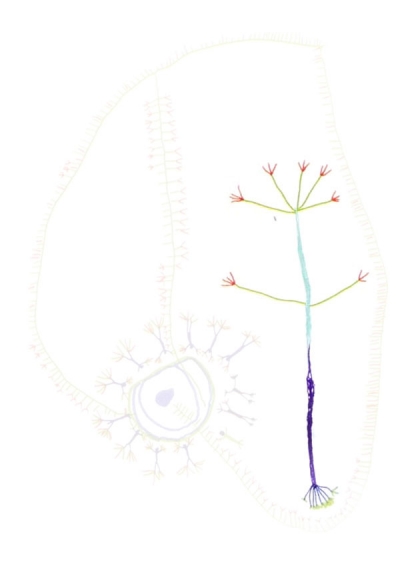

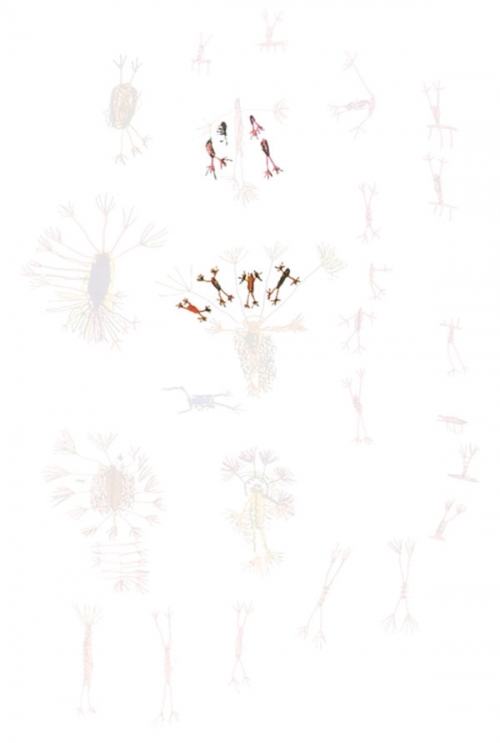

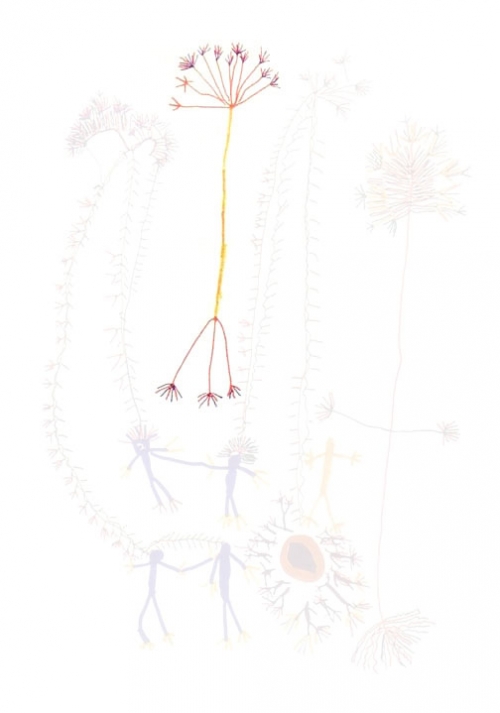

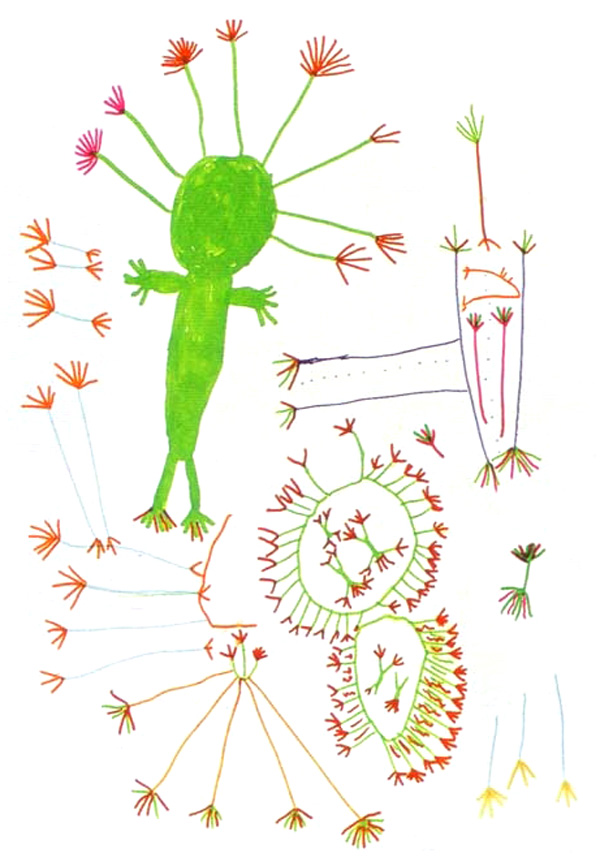

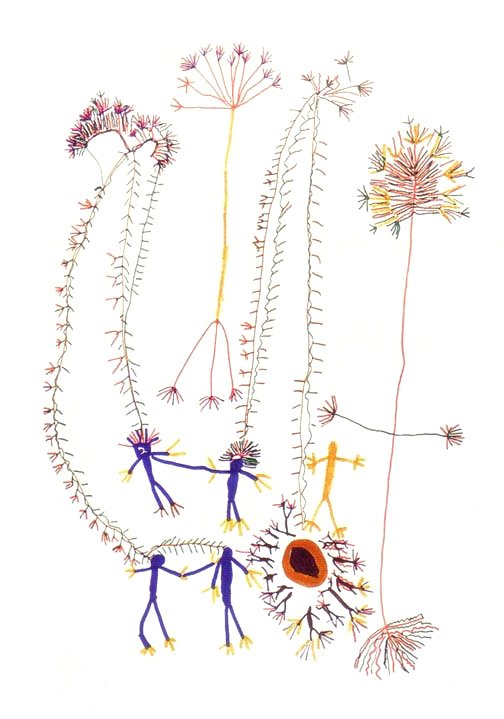

draw 37 Orlando

Subtitle

The home of spirits – Hekurap

The philosopher Gilbert Simondon defined the magic mode of existence “as that which is pre-technical and pre-religious, immediately above a relation that is simply that of the living being with its environment.” [3] Evidently, this does not concern a primary, crude relation, that would be “surpassed” with the end of the magical phase and the advent of other later modes of existence; rather, it signifies a primeval man-world relation, the most intimate relation that can be conceived between the human and the environment, rather than a separation that detaches the figure from the background. For this very reason, the magical mode of existence is characterized as a time of metamorphosis, as a flow, a continuum of transformations and individuations, in which the past, present, and process of becoming coexist. A mode of existence in which the tensions and powers of the virtual find resolution, produce meaning, and are actualized through contact and cross-influence, by disparation, information, and invention.

[3] Gilbert Simondon, Du mode d’existence des objets techniques (Paris: Aubier/Montaigne, 1969), 156.

The reader-viewer can, on his own, perceive in the Yanomami image-drawings how the magical mode of existence functions and how the magical thought is expressed in the captions that accompany them, most of them recorded by Carlo Zacquini. These do not explain them, but are rather involved in what is happening in this segment of the flow of the real that was captured and projected on the paper. The reader-viewer needs to understand that the language expressed by the magical thought does not represent the magical mode of existence of the image- drawings, just as the latter, in turn, do not represent a reality outside of that mode. Indeed, we do not find ourselves in any way within the realm of representation, but rather in what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari denominated as the wild material-semiotic realm of signs, whose socius is the land. Therefore, when we look at the drawings, we must bear in mind that their motive is that which the Yanomami call the forest-land.

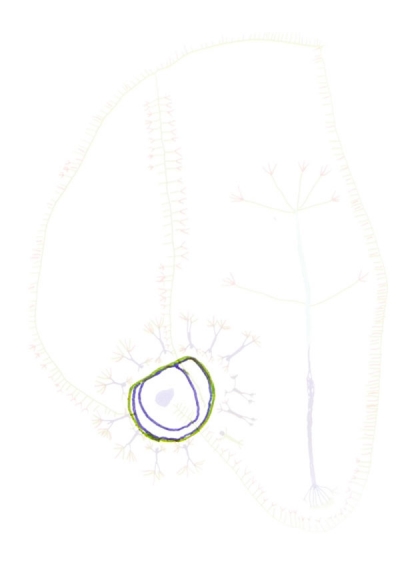

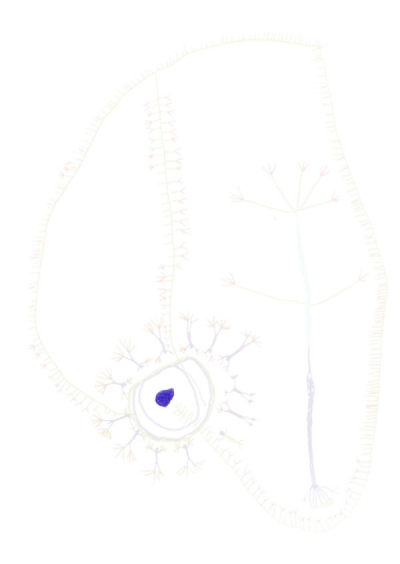

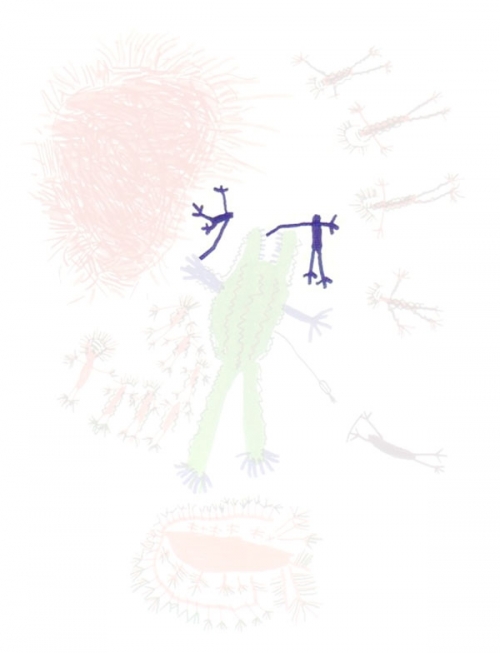

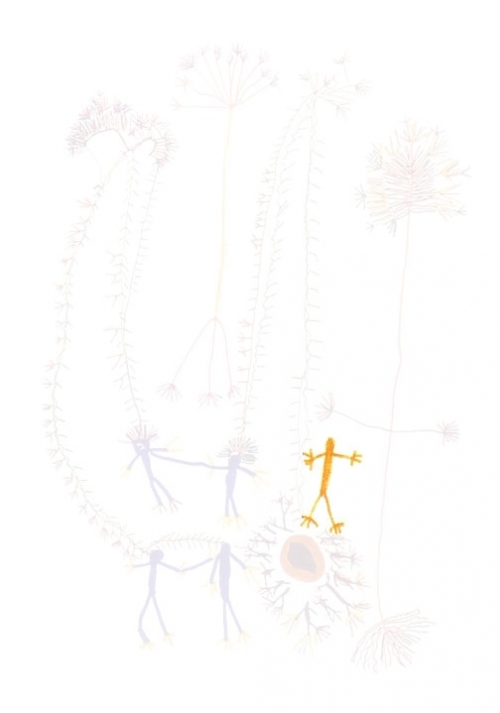

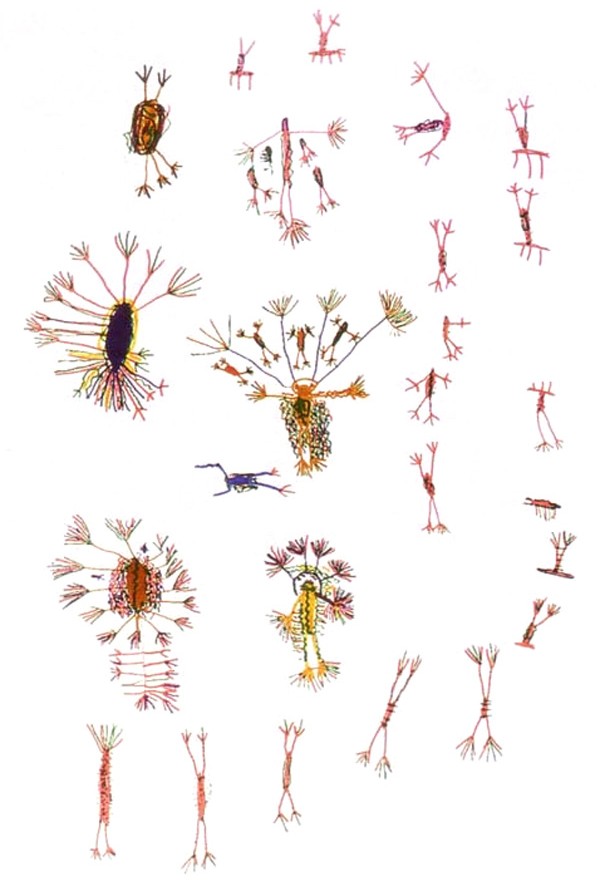

draw 38 Orlando – The home of the spirits

Subtitle

- The moon – Poripo

- The home of the spirits

- Xapiris and paths

The term forest-land cannot and should not be confused with the meaning that we assign to the word land, and cannot be translated as such. There is an insurmountable ontological and epistemological difference between them, and this difference prevents the land from being objectivized and appropriated by men, who for their part become subjects who are separated, aloof from it. In his text “L’esprit de la forêt,” Bruce Albert explains what the Yanomami understand by “forest”: “In the Yanomami language the word urihi a simultaneously denotes the tropical forest and the soil on which it grows. Through a series of links, it also refers to an idea of open and contextual territoriality. Thus, the expression ipa urihi, “my forest-land,” can denote the region of birth or current residence of a speaker (as a scope of use), while yanomae thëpë urihipë, “the forest-land of human beings (Yanomami)” comes closer to our idea of the “Yanomami lands,” and urihi a pree, “the great forest-land,” refers to an all-encompassing space akin to our concept of “Earth.” As an inexhaustible reservoir of resources indispensable to their existence, this “forest-land” is not, however, in any way for the Yanomami an inanimate and mute scenario located outside society and culture, an inert nature that is subject to human will and exploitation. Rather, it is a living entity endowed with a shamanic spirit-image (urihinari), a vital breath (uixia), and an inherent potential for growth (në rope). It is moreover animated by a complex dynamics of exchanges, conflicts, and transformations between the different categories of beings—human and nonhuman, visible and invisible—that inhabit it.” [4]

[4] Bruce Albert, “L’esprit de la forêt,” in Yanomami l’esprit de la forêt, Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain (Paris: Actes Sud, 2003), 46.

This forest-land therefore bears a real dimension and a virtual dimension in constant interaction, which do not seem to accept a separation between the transcendent and innate planes, at least as we understand them, since transcendence and innateness are part of our “one and the same economy of metamorphoses,” to recur to the expression by Bruce Albert. In this sense, the forest-land cannot be confused with a landscape, an “environment” or an area objectivized as a mere source of resources, whose existence is only justified because it can provide humans with their survival or enrichment. The meaning of the forest is in no way one-dimensional. For this reason, the words of the shaman complement those of the anthropologist: “What you call nature, in our language is urihi a, the forest-land, and its image, which the shamans see, the urihinari. The existence of this image is what makes the trees live. What we call urihinari is the spirit of the forest: the spirits of the trees, huutihiripë, of the leaves, yaahanaripë, and the vines, thoothoxiripë. These spirits are very numerous and play in the soil of the forest. We also call them urihi a, nature, just like the animal spirits, the yaroripë, and even those of the bees, the turtles, and the snails. The forest’s fertility, në rope, is also nature for us: it was created with this, it is its wealth.”[5]

[5] Davi Kopenawa, “Urihi a,” in Yanomami l’esprit de la forêt, 51.

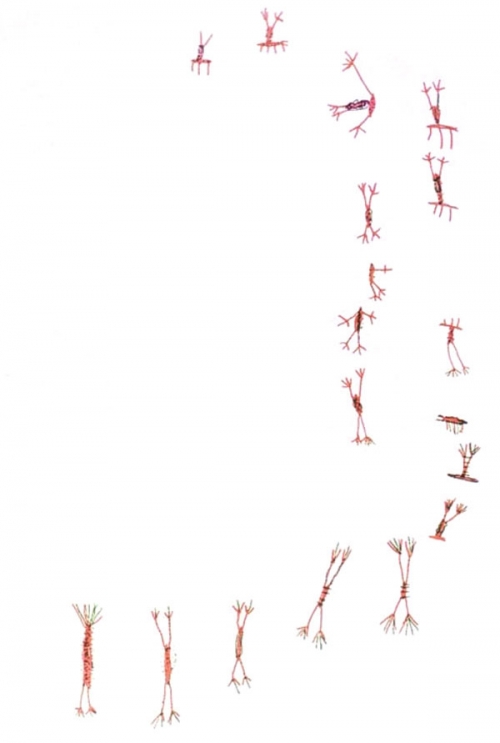

draw 27 Titi – The night

Subtitle

- The night in the middle – ñoro

- The night in the beginning – weya

- The very dark night – pata

- The night is born (shortly after sunset)

- The night’s wife eats sons

- The sons

- The young daughters of the night

Land, forest, humans, spirits, animals, and plants are thus understood within the meaning of the forest-land. This is what is found in the Yanomami image-drawings. But there is yet a last point, which the reader- viewer should be aware of. This is the status of the image in the Yanomami cosmology and culture. It is essential to understand the role of the image in shamanism, mentioned by Davi Kopenawa, because the image-drawings bear a very strong correspondence and resonance with what the shamans see in their rituals. On the other hand, it is necessary to underscore that Taniki, Koromani Waika, and Davi Kopenawa are shamans, that Domingos is the son of a shaman… Finally, it should be noted that literacy, even in the mother language, brings about an interference in the lines of the drawing, as can be observed in the works of the latter artist, for example, made in the 1990s.

What is the image in Yanomami shamanism? Bruce Albert writes: The images (utupë) that the Yanomami shamans “invoke,” “bring down,” and “make dance”—in a dream or trance—are (essentially but not exclusively) the ancestral “humanimals” that lived in the times of the origins…. It is said that such images constitute the “specter value” of the primordial beings endowed with a human “skin” (body) and with an animal name (identity). They are perceived by the shamans in the form of an infinite multiplicity of tiny humanoids, decorated with body paintings and dazzlingly bright ornaments. Such corpuscular image-beings, a sort of mythological quanta, inhabit the world in a free state, caught up in a ceaseless activity of games, exchanges, and wars that sustain the dynamics of the visible phenomena. Once installed, during the initiation, in a celestial dwelling associated with the young shaman, they become his “sons,” a “kindred” form of humanimal images of the “first time.” They are then, according to the ethnographic jargon, “auxiliary spirits” (xapiri pë). Once the xapiri pë are tamed in this way they are selected and combined in each shamanic session, according to their attributes and skills…”[6]

[6] Bruce Albert, “Images, traces et ‘hyper images’: impromptu d’ethnographie noctambule,” 1. Available at www.ctrlab.inf.br/Arquivos/ Hyper%20images%20yanomami_BA_5.7.11.pdf, in French.

In the understanding of B. Albert, this mode of the fundamental image-being constitutes the center of gravity of Yanomami ontological and cosmological thought. The anthropologist also points out that the shamanic images, dreamed or induced by hallucinations, should not be classified as what we call “mental images” (mirages, inner visions), since they are described by the shamans as direct perceptions of an outer, absolutely tangible reality. On the other hand, Bruce Albert states with precision: This does not involve a phenomenon of representation, but rather a process for the presentification of the invisible…. Neither replicas, nor metaphors, the utupë images are above all ontological states whose intermittent visibility is made effective during the shamanic session by an effect of corporal transduction.”[7]

[7] Bruce Albert, “Images, traces et ‘hyper images,’” 4.

Everything takes place, therefore, as though the Yanomami image-drawings were configured as projections of the capture of utupë images that non-shamans and non-Yanomami can have access to, because instead of coming down and passing through the shaman’s body without leaving a trace, they do this coupled to an expressive device that can make their occurrence visible and memorable. This does not mean to say that the image- drawings are the utupë images. These latter we will never see, they remain inaccessible. But we can consider the image-drawings as an echo of them, an echo of their passage.

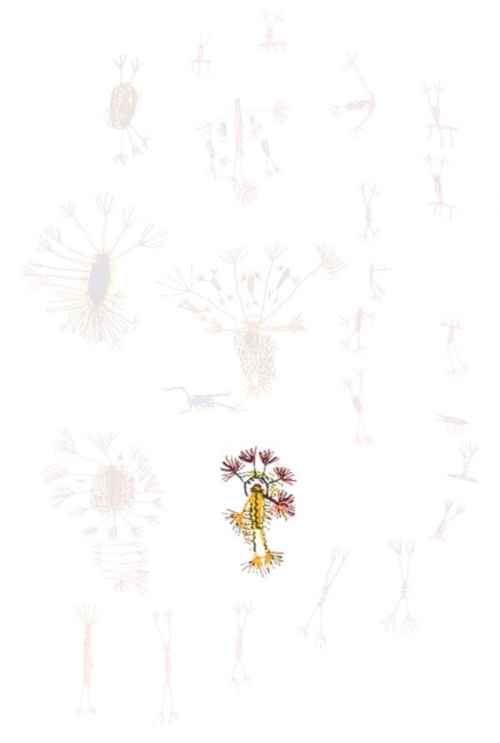

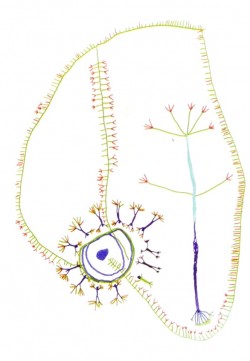

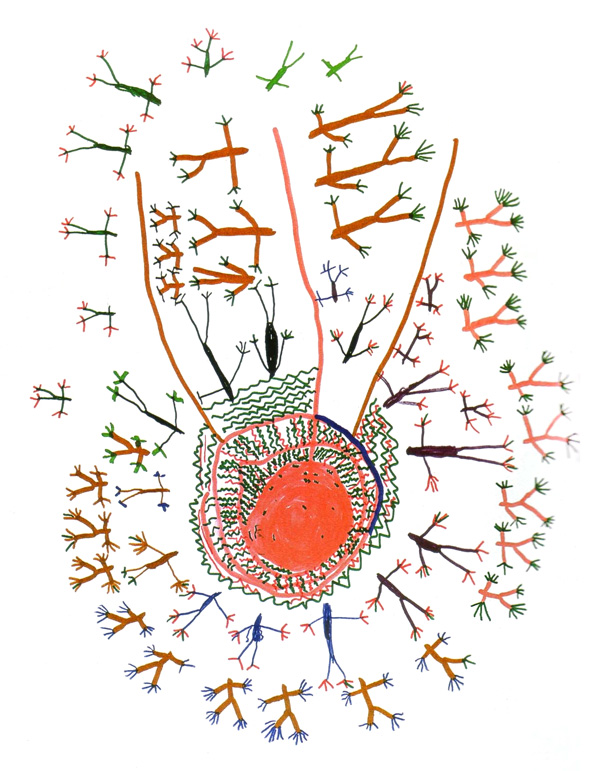

draw 22 Orlando

Subtitle

Motoka and sons

Becoming visible, being projected in the blank space, the image-drawings inscribe the forest-land onto a surface that transfigures the sheet of paper, taking it to the limit of its topology. Indeed, beyond the magic—or, to put it better, because of it—the Yanomami drawings make us think, and raise a perturbing question. This is what can be seen in philosopher David Lapoujade’s reflection concerning them, in our conversations in Watoriki, when he spoke of the multiplicity of perspectives that confers consistency to the image:

“Returning to the drawings, there is a question that cannot be considered only in light of the real and the virtual. It is something that seems very important to me, and which Bruce briefly mentioned: it is the image… it is the fact that it concerns something impossible… from the standpoint of the coexistence of perspectives that are incompatible in terms of representation. And these incompatibilities that are, nevertheless, in the smallest drawing, seem very rich to me, perhaps even richer than the real-virtual question, or the question of whole-part, power, etc. Because insofar as it makes them coexist, this coexistence of perspectives “adjusts” the planes, “arranges” them in each other: the perceptive plane with the cosmological plane and with the intensive plane and with the… nonrepresentative but figurative plane, that is, the more precisely visual plane, in the shamanic states. If there is something that Western art never knew how to do, despite all its audacity, it is this sort of thing…. This insertion at the border of topology (since they are incompatible spaces) is above all the most interesting aspect and, it seems to me, the most startling, and innovating one, as well as that which is most in rupture with Western art.”[8]

[8] Stella Senra, “Conversações em Watoriki – Das passagens de imagens às imagens de passagem: captando o audiovisual do xamanismo,” in Cadernos de subjetividade (São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas da Subjetividade, PUC/SP), year 8, no. 13 (October 2011): 76.

draw 25 Orlando – Revenge of Sihirim

Subtitle

- Sihirim shoots the arrow

- Poripo is eating children

- Children

- A lot of blood floods generating Yanomamis

- Yanomamis

- Poripo sleeps in a beautiful hammock

Listening to Lapoujade, Bruce Albert adds that the drawings are a multi-perspectivist spontaneous agglomeration, that the entire Yanomami territoriality is a linkage of points of view and that everything is interconnected, inserted in a multiplicity of spatial and temporal perspectives. Reiterating that this effectively concerns a topology, David Lapoujade concludes:

“So, it means that there is never a single image… There are always various images. It should actually be called a multi-image.”[8]

[8] Stella Senra, “Conversações em Watoriki – Das passagens de imagens às imagens de passagem: captando o audiovisual do xamanismo,” in Cadernos de subjetividade (São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas da Subjetividade, PUC/SP), year 8, no. 13 (October 2011): 76.

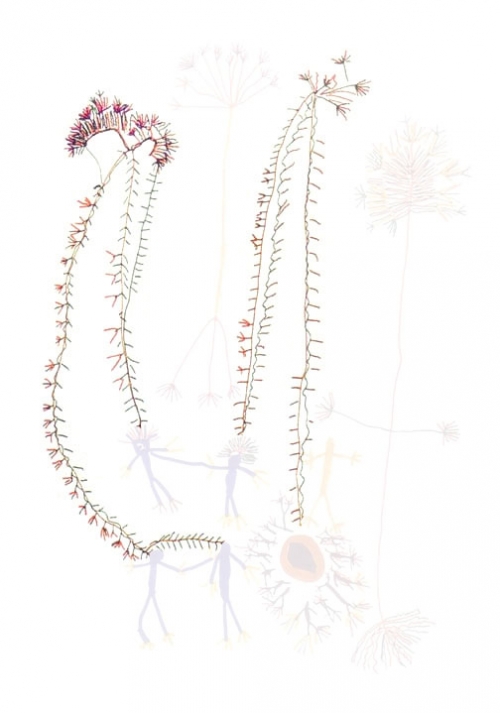

draw 26 Orlando

Subtitle

- Trees of ñakoana

- Trees of “mamokori” (kurare)

- “Ripurusiri”

- The “Xapuri hekurap” come down to take ñakoana following a long path from above

- Paths

- The Xapuri take the powder of the Kurare,

- Powder of Kurare.

These sorts of comments about the relevance of the topological question evidently reiterate Francis Alÿs’s finding about the mode in which the drawing occupies space. And this becomes even more fascinating when Carlo Zacquini, who saw Taniki and Koromani in the process of drawing, states that the vertical or horizontal position of their drawings generally has no importance. Because while they are executing them they turn the paper this way and that, giving the observer the impression that the drawing is being made upside down…

draw 28 Orlando

Subtitle

The mutum (paruri) which symbolizes night (titi).

Note. This drawing was also referred as the descent of xapiri pë.

Santos, Laymert Garcia. “Projections of the Forest-Land: The Yanomami Image-Drawing”. In Anjos, Moacir dos (editor). Belonging – Cadernos SESC_Videobrasil 8. São Paulo: SESC, 2012-2013, pp. 55-68. Translation: John Norman, Bruno Gambarotto.

Other drawings were included in the printed publication. Drawings selected for this website by Orlando Nakeuxima Manihipi-theri, 1976 (Collection Laymert Garcia dos Santos and Stella Senra).

Bibliography

ALBERT, Bruce. Yanomami l’esprit de la forêt. Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain. Paris: Actes Sud, 2003.

______. La chute du ciel. Paroles d’un chaman Yanomami. Coll. Terre Humaine. Paris: Editions Plon, 2010.

______. “Images, traces et ‘hyper images’: impromptu d’ethnographie noctambule.” Available at HYPERLINK “http://www.ctrlab.inf.br/Arquivos/Hyper%20images%20yanomami_BA_5.7.11.pdf” www.ctrlab.inf.br/Arquivos/Hyper%20images%20yanomami_BA_5.7.11.pdf.

______. “Taniki” and “Joseca.” In: Histoires de Voir. Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2012.

ANDUJAR, Claudia, Carlo Zacquini, and Emilie Chamie. Mitopoemas Yãnomam. São Paulo: Olivetti, 1978. Comissão Pró-Yanomami.

Yama ki hwërimamouwi thë ã oni – Palavras escritas para nos curar. Escola dos Watoriki theri pë. Watoriki: CCPY/MEC/PNUD, 1997.

DELEUZE, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. L’AntiOedipe – Capitalisme et schizophrénie. Paris: Minuit, 1972.

KOPENAWA, Davi. “Urihi a.” In: Albert, Bruce. Yanomami l’esprit de la forêt. Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain. Paris: Actes Sud, 2003.

SENRA, Stella. “Conversações em Watoriki – Das passagens de imagens às imagens de passagem: captando o audiovisual do xamanismo.” In: Cadernos de subjetividade. São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas da Subjetividade, PUC/SP, year 8, no. 13, October 2011.

SIMONDON, Gilbert. Du mode d’existence des objets techniques. Paris: Aubier/Montaigne, 1969.

This post is also available in:

![]() Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Português (Portuguese (Brazil))